This is the first installment of a blog series entitled “No family should go through this,” which details the story of J.A., a 14-year-old whose mistreatment at the hands of Burlington police and fire officials highlights the consequences of unchecked racial bias and ableism in the City’s first response system. When we advocate for police oversight and accountability, it’s to prevent cases like this one from ever happening.

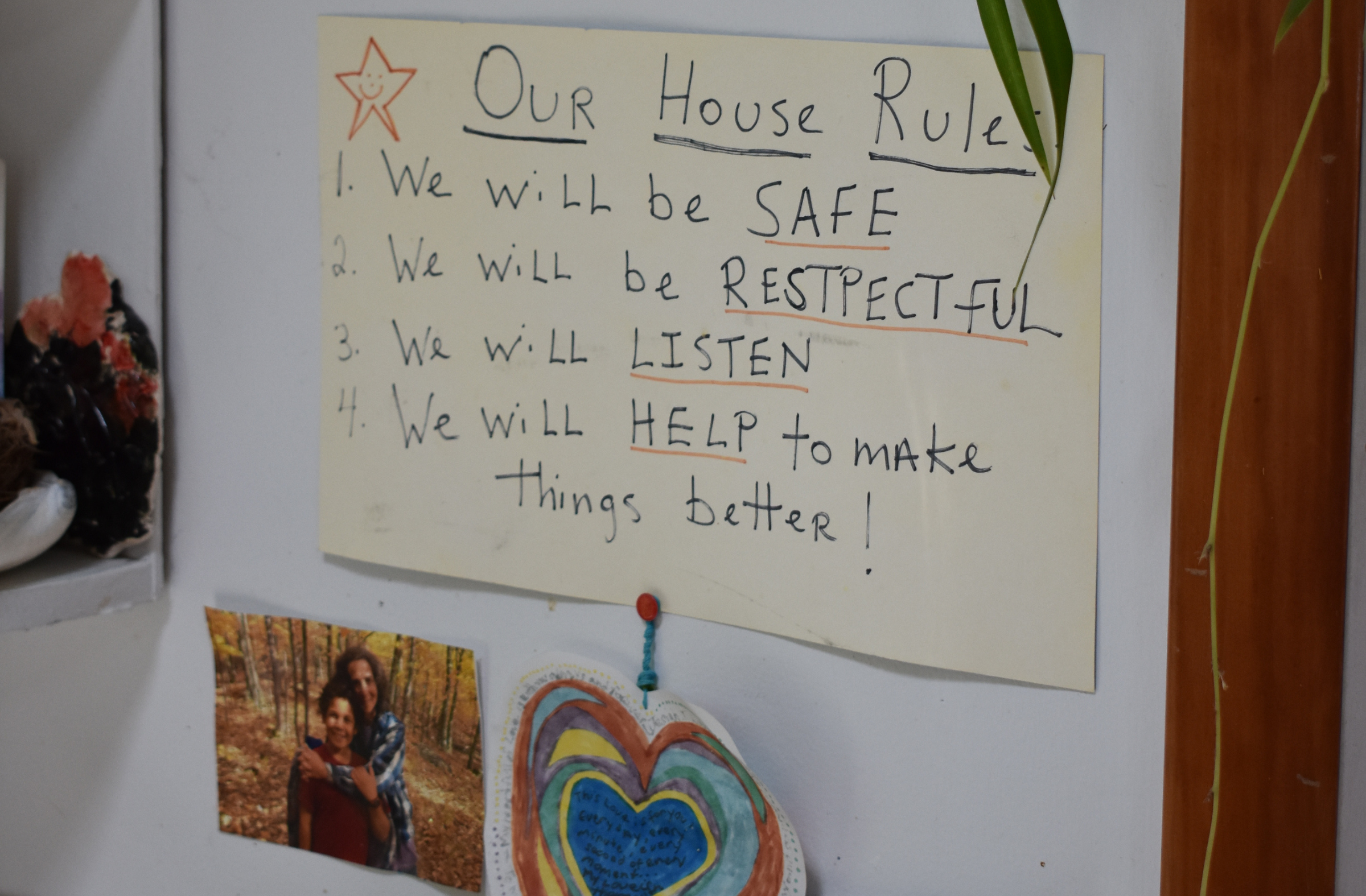

Nestled in a historic Burlington neighborhood, Cathy Austrian’s light-filled home features photos of her child, J.A., in almost every corner, interspersed with artwork the pair has created over the years. Tacked up above the kitchen table is a hand-written poster that outlines the family’s house rules—to help others, to listen, to be safe, and to treat people with respect. Nearby lies another poster made by J.A., which reads: “The most powerful force in the universe is our love, always joining us together.”

On a Saturday in May 2021, this family’s safe haven became the site of a life-altering injustice against then-fourteen-year-old J.A., when Burlington police and paramedics needlessly escalated what should have been a routine call for support into a nightmarish event.

Over the course of a brief encounter with city officials, J.A. was verbally threatened, physically restrained with excessive force, injected with ketamine (a powerful and potentially deadly tranquilizer), and removed from his home in a stretcher bag as his mother watched in horror.

Burlington police were not called to a crisis—they created one.

J.A., a Black teenager with a history of complex trauma and both intellectual and behavioral disabilities, was having an especially hard time in the weeks leading up to that day in May. In part, he was adjusting to a change in his attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication and had recently been acting out of character.

When Cathy learned that J.A., then a middle school student, had taken several vape pens from a local gas station earlier that day, she was concerned. She called the police for support and two Burlington Police Department officers arrived at their home.

Cathy believed and expected that a conversation with the officers would help J.A. better understand the impact of his actions. She immediately informed the officers of her child’s disabilities, ongoing medical issues, and the fact that he had recently undergone an MRI of his heart.

When BPD officers entered J.A.’s room, he was sitting calmly on his bed and voluntarily relinquished all but one of the vape pens. Although J.A. presented no danger to the officers or to himself—and despite their knowledge of J.A.’s disabilities and recent medical history—the officers quickly lost patience, threatening to handcuff and arrest J.A. if he did not produce the final item.

Officers then abandoned Burlington Police Department policies and de-escalation techniques as they grabbed J.A., wrenched his arms behind his back, and took the last pen out of his hands. When J.A. started to panic, the officers did not disengage. Instead, they handcuffed J.A., pushed him back onto his bed, and ultimately pinned him to the floor, where the frightened teen screamed and twisted his body in distress.

“I could not keep my child safe, even in my own home.”

Officers restrained J.A. in this position for more than 20 minutes as they waited for paramedics from the Burlington Fire Department. Upon arrival, the paramedics covered J.A.’s head with an opaque mesh “spit hood,” further terrifying him.

The paramedics did not evaluate how J.A.’s disabilities were contributing to his distress at being forcibly restrained and hooded. Instead, they decided he was experiencing “excited delirium,” an illegitimate diagnosis rejected by the medical community yet often applied to victims of police violence—especially Black men and boys—as seen in several high-profile policing incidents.

For J.A., the misdiagnosis of excited delirium resulted in both excessive force and forced drugging. Cathy watched, terrified, as paramedics injected her child with a powerful and fast-acting sedative called ketamine. Unconscious, J.A. was carried from his room in a stretcher bag and taken to the hospital while Burlington police returned the vape pens. J.A. was discharged the next day—bruised, disoriented, and traumatized.

In search of accountability—and a call for change

After J.A.’s experience, Cathy Austrian filed an official complaint against the Burlington Police Department for unwarranted and excessive force used against her child. After reviewing her complaint, as well as body camera footage and the confidential results of BPD’s internal investigation, the Burlington Police Commission made several recommendations to then-acting police chief Jon Murad.

Chief Murad did not accept the Commission’s recommendations in full and concluded that the BPD officers’ actions constituted an appropriate use of force. He told Cathy that his officers had not violated any department rules, even though they had.

Rather than accept responsibility for the incident, Burlington sought to refer J.A. to the Burlington Community Justice Center for assault. But the Center rejected the charge, determining J.A. was not at fault, and it was never pursued.

Cathy then filed a lawsuit in Vermont state court on behalf of her child, who is still a minor, with representation from the ACLU of Vermont and Latham & Watkins LLP, with strategic support from the MacArthur Justice Center.

By filing this lawsuit, Cathy hopes the City of Burlington will take seriously its obligation to root out biases—particularly racism and ableism—in the policies, procedures, and actions of its first response units. These include ensuring that people with disabilities receive proper accommodations during interactions with the police and other first responders; addressing stereotyping and biases that underlie the race-based disparate treatment that J.A. endured; and prohibiting the use of ketamine to treat “excited delirium” in the field.

The ACLU has long worked to bring more oversight and accountability to policing in Vermont, and J.A.’s story is a powerful reminder that the status quo is actively harming many of our neighbors, particularly people of color and people with disabilities. We are honored to support Cathy in her pursuit of justice—and will continue to work in the courts, in the legislature, and in our communities to reimagine policing in Vermont.